Pocillopora meandrina, commonly known as the cauliflower coral, is a species of reef-building stony coral found throughout the Indo-Pacific and Pacific Oceans, including the Maldives. It inhabits shallow reef environments and is recognised by its compact, cauliflower-like colonies covered with wart-like skeletal projections. The species is widespread and ecologically important, contributing to reef framework formation, habitat complexity, and reef recovery following disturbance.

Description

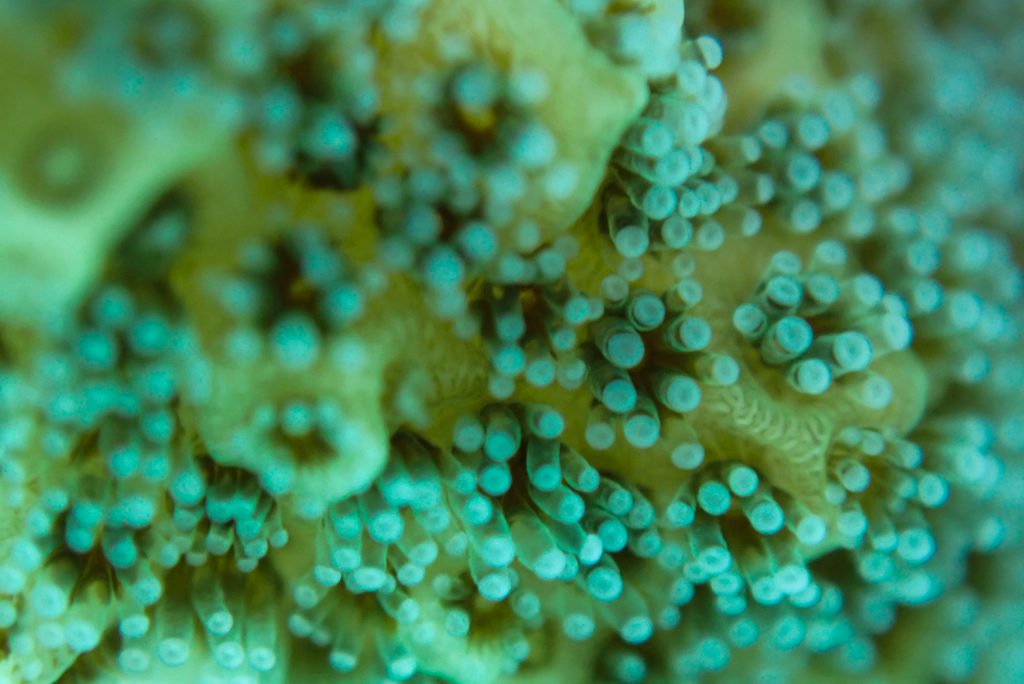

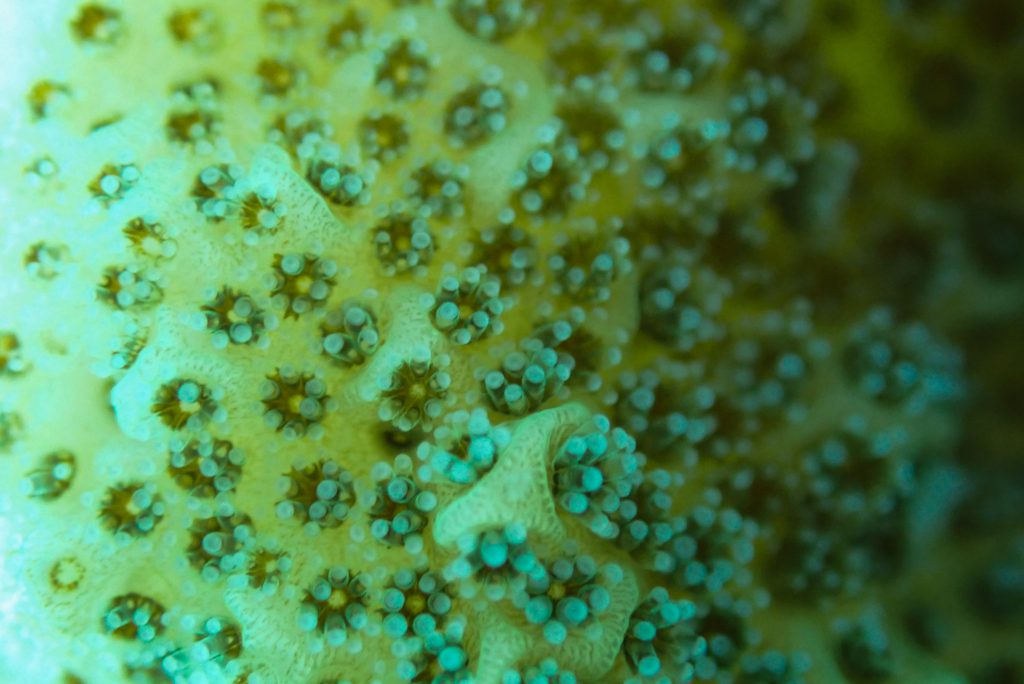

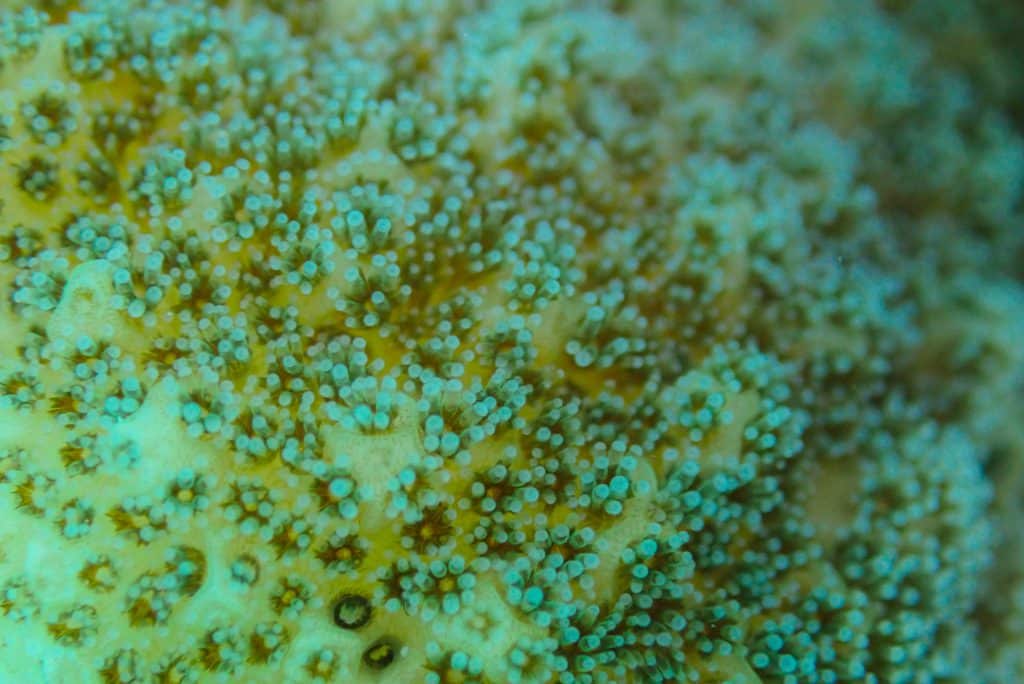

Colonies of Pocillopora meandrina are variable in form but are most commonly compact and dome-shaped, forming rounded or irregular masses composed of short, thick lobes. In some environments, particularly where water movement is stronger, colonies may develop flattened ridges or convoluted surfaces. The skeletal surface is characterised by numerous verrucae, which are wart-like protrusions formed by clusters of corallites. These verrucae give the coral its distinctive rough texture and enhance structural strength by dispersing mechanical stress caused by waves.

Colouration varies according to environmental conditions and the density of symbiotic algae within the tissues. Colonies are typically brown, yellow-brown, greenish-brown, or occasionally pink. During bleaching events, colonies may lose pigmentation and appear pale or white.

Scientific classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Cnidaria

Subphylum: Anthozoa

Class: Hexacorallia

Order: Scleractinia

Family: Pocilloporidae

Genus: Pocillopora

Species: P. meandrina

Binomial name

Pocillopora meandrina

Dana, 1846

Polyp structure and biology

The living surface of Pocillopora meandrina is composed of thousands of minute polyps distributed across the colony. Each polyp occupies a shallow skeletal depression known as a corallite and is extremely small, usually below the threshold of visibility for the unaided human eye underwater. As a result, the coral often appears solid and rock-like during normal reef observation.

At micro-scale magnification, each polyp consists of a central oral disc surrounded by a ring of short, compact tentacles. These tentacles are stubby and densely arranged, distinguishing the species from corals with long, flowing tentacles such as Goniopora. The tentacles contain nematocysts, specialised stinging cells used to capture microscopic plankton and suspended organic particles. Captured prey is transferred to the mouth, where digestion begins.

The oral opening also functions in gas exchange and the expulsion of metabolic waste. Polyps within a colony are interconnected by living tissue, allowing nutrients and energy to be shared throughout the colony and enabling the coral to function as a single biological unit despite being composed of many individual animals.

Symbiosis and nutrition

Like most reef-building corals, Pocillopora meandrina maintains a symbiotic relationship with photosynthetic dinoflagellates, commonly referred to as zooxanthellae. These algae live within the coral’s tissues and produce energy-rich compounds through photosynthesis, supplying the majority of the coral’s metabolic requirements. In return, the coral provides the algae with shelter, access to sunlight, and inorganic nutrients.

In addition to photosynthetic nutrition, the coral feeds heterotrophically by capturing planktonic organisms and organic particles using its tentacles. This dual nutritional strategy allows the species to persist across a wide range of environmental conditions.

Reproduction

Pocillopora meandrina is a hermaphroditic species. Larvae develop internally within the polyps and are released into the surrounding water once fully formed. These larvae remain free-swimming for several weeks before settling on suitable substrate and beginning skeletal growth.

The species is also capable of asexual reproduction through fragmentation. Broken portions of colonies may reattach to the substrate and continue growing as independent colonies, contributing to rapid recolonisation following physical disturbance.

Distribution and habitat

Pocillopora meandrina occurs widely across the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It inhabits a range of reef environments, including exposed reef fronts, protected lagoons, and lower reef slopes. The species typically grows on hard substrates such as coral rock and consolidated rubble in shallow, well-lit waters.

In the Maldives, it is common across many atolls, including Noonu Atoll, where it is frequently encountered on reef flats and lagoonal reefs. Its tolerance of varying water movement and light conditions contributes to its broad distribution.

Ecological role

As a reef-building coral, Pocillopora meandrina contributes significantly to reef framework development and long-term carbonate accumulation. Its complex surface structure provides habitat and shelter for a variety of small invertebrates and juvenile reef fish. The species is often among the corals that recolonise disturbed reef areas and therefore plays an important role in reef resilience and recovery.

Micro-scale documentation

Micro-scale biological features of Pocillopora meandrina can be documented using specialised close-focus underwater imaging techniques. Micro-scale imaging enables the observation of individual polyps, tentacles, and oral discs that are otherwise invisible to the human eye during normal reef observation. This non-destructive approach provides valuable insight into coral feeding behaviour, tissue condition, and functional anatomy in natural reef environments and complements traditional skeletal and laboratory-based studies.

Threats

Like many reef-building corals, Pocillopora meandrina is vulnerable to rising sea temperatures, which can cause coral bleaching through the loss of symbiotic algae. Additional threats include ocean acidification, pollution, sedimentation, and physical damage from human activities. Long-term survival of the species depends on effective reef conservation and global efforts to mitigate climate change.

Conservation status

Pocillopora meandrina is currently listed as Least Concern (LC) under the IUCN Red List (version 3.1), reflecting its wide distribution and overall abundance. However, local populations may decline where reefs are subjected to severe or repeated environmental stress.